In late December 2024 to early January 2025, NSW firefighting authorities faced a run of numerous bushfires in remote locations. Most if not all were ignited by lightning. On 27 December storms swept over the Blue Mountains and about a dozen fires popped up across the northern parts of Wollemi and Yengo national parks and adjacent bushland.

Other fires occurred in remote parts of Blue Mountains, Kosciuszko and Oxley Wild Rivers national parks. With no access for ground vehicles, all these fires had to be managed with aerial attack and remote area firefighter teams (RAFT) taken to the fireground by helicopter. Fortuitously, although the weather was sometimes hot, overall firefighting conditions were moderate.

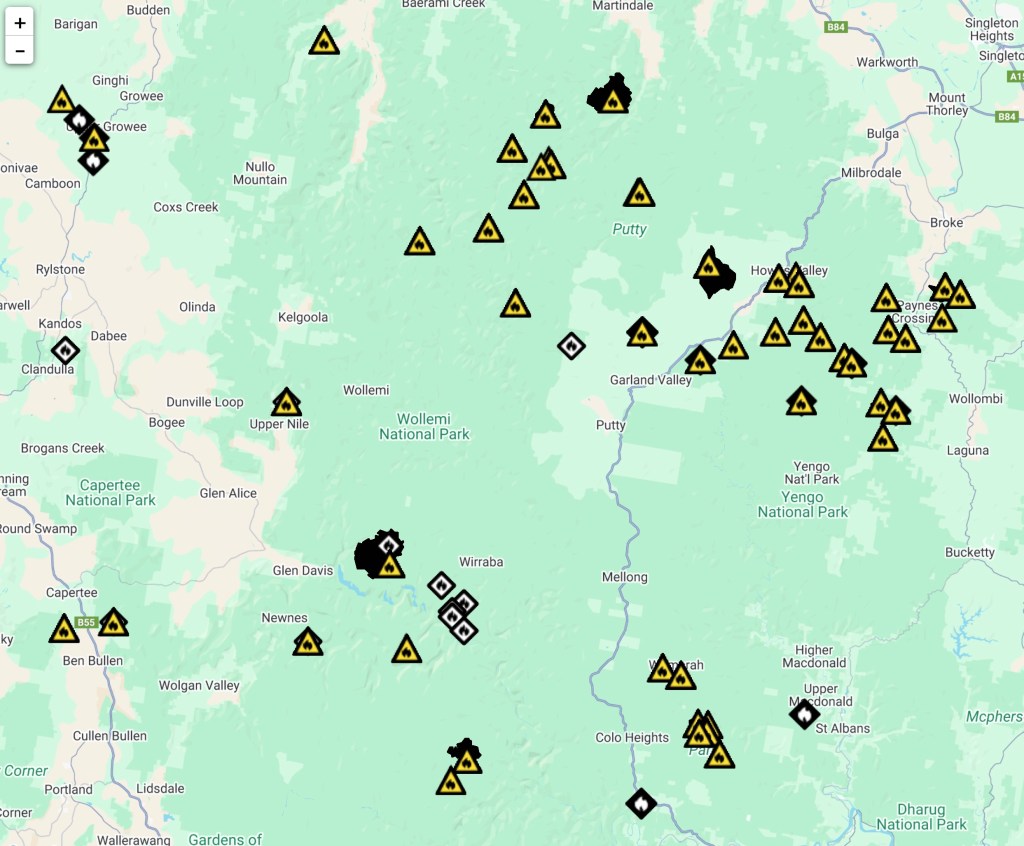

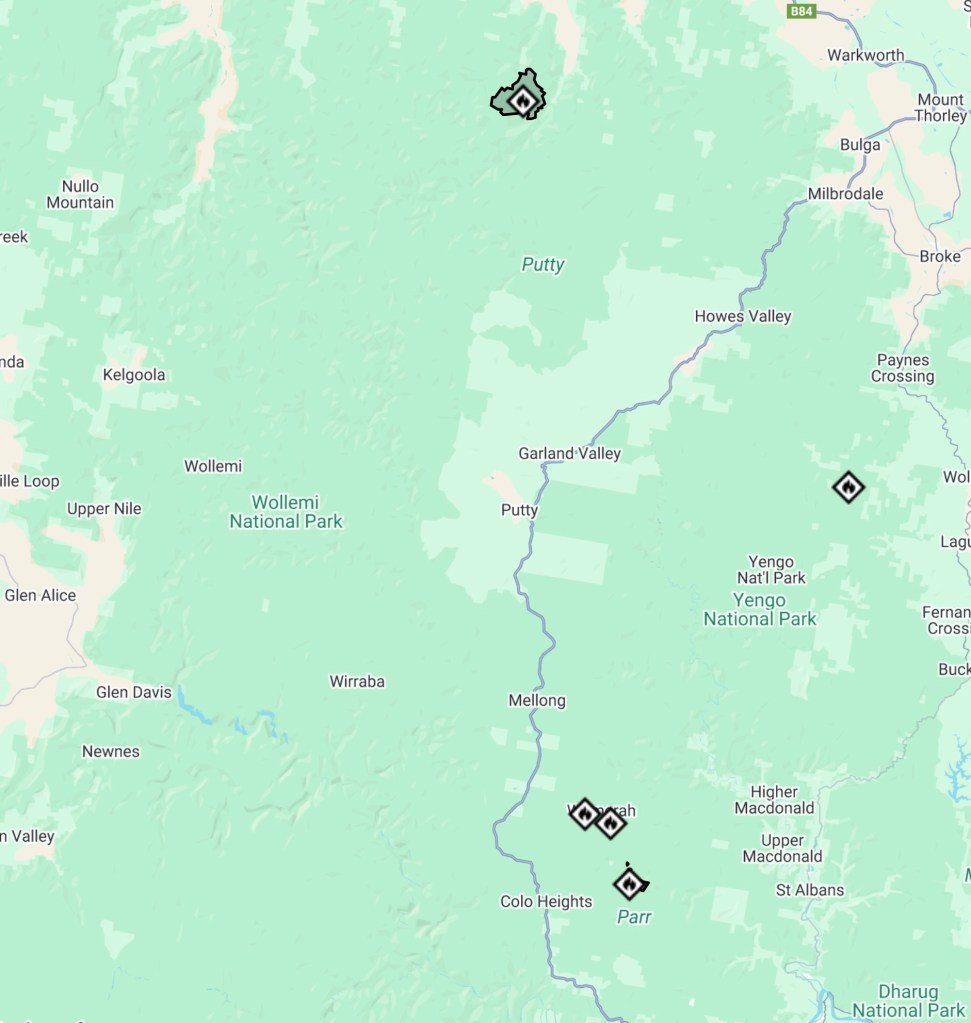

More storms on 5 January brought more ignitions. At one stage there were more than 30 fires burning in the northern Blue Mountains, in the ‘Yengo-Wollemi Complex’ and further south. So many fires fires in the region has not been exceeded since 1997. While details are hard to come by (see below), it seems that while many of these fires were initially under NPWS management, all the Yengo-Wollemi fires were eventually placed in RFS control under three section 44 declarations, in Singleton-Muswellbrook, Lithgow and Hawkesbury LGAs. This generated large multi-agency campaigns.

At one stage, RFS Facebook posts said that 500 firefighters, IMT members and support teams were engaged in the effort, and on 6 January that 1.2 million litres of water per day was being transported onto the Singleton-Muswellbrook fires. Firefighters came from RFS, NPWS, Fire and Rescue and Forestry Corporation. This was perhaps the largest and most complex bushfire operation in NSW since Black Summer 2019-20. It received little to no mainstream media coverage, probably because no property was under imminent threat and high profile fires were running in Victoria at the time.

Most if not all of the fires were in areas burnt in Black Summer, raising concerns in some nearby communities that had been impacted. Some of the fires were quickly contained, while others spread and became ongoing challenges. Triage came into play, and resources were prioritised to fires according to the risks each one posed. Aerial attack (bombing with water, foam or retardant) can ‘knock down’ a fire, but only people on the ground or substantial rain can finish the job. The holiday period would have made mustering the large numbers of RAFT needed from NPWS and RFS more difficult.

The largest fires grew to 1908 hectares (Dingo Creek, Wollemi NP) and 1796 hectares (Yarrowitch Trail, Oxley Wild Rivers NP) before being contained. In an impressive effort, nearly all fires were contained before rain stopped most play on 7 January. Continued rain saw all fires extinguished.

IBG comment

- As probably the largest NSW fire operation since Black Summer, the Yengo-Wollemi Complex is a great opportunity to review how bushfire operations have improved or changed, especially for remote fires. The diversity of fires and possibly also differences in how they were managed would allow useful comparison of the most effective responses, strategies and tactics.

- Given the paucity of past fire analysis by either RFS or NPWS, IBG is not confident that it will happen in this case. After Action Reviews, debriefs and lessons processes may now be in place across all agencies, but a proper understanding of time-and-event and the effectiveness of operations must be based on more than what people say. Hard evidence is essential, in the form of detailed record-keeping followed by objective analysis.

- This run of fires in moderate conditions would have given numerous firefighters, leaders and support people a lot of valuable experience that should be built on with good analysis and review.

- Since Black summer, IBG has strongly advocated for faster and stronger initial attack, especially on remote fires that can get out of hand quickly and create huge suppression problems. Bushfire authorities have expressed and adopted this mantra, and there has been an expansion of aerial resources and also RAFT numbers in RFS and NPWS. Multiple ignitions are a challenge to whatever preparations are in place, and it is as yet unclear how well the theory has translated into practice across these fires. Even if adequate resources are available, they need to be backed up with the right protocols and speed and weight of response.

- Official media coming out of RFS head office emphasised the role of RFS resources, especially aircraft and volunteers, however much of the RAFT work was done by NPWS staff firefighters. This corporate emphasis is understandable, but in section 44 fires RFS is in complete control of multi-agency operations and also public information which requires a more objective approach. However local RFS section 44 commands, such as in Lithgow (Chifley) and Tumut (Riverina Highlands), often highlighted the role of NPWS, Fire and Rescue, Forestry and other players in their own media. Giving due recognition to all participant is important in maintaining the morale and effectiveness of the entire bushfire industry.