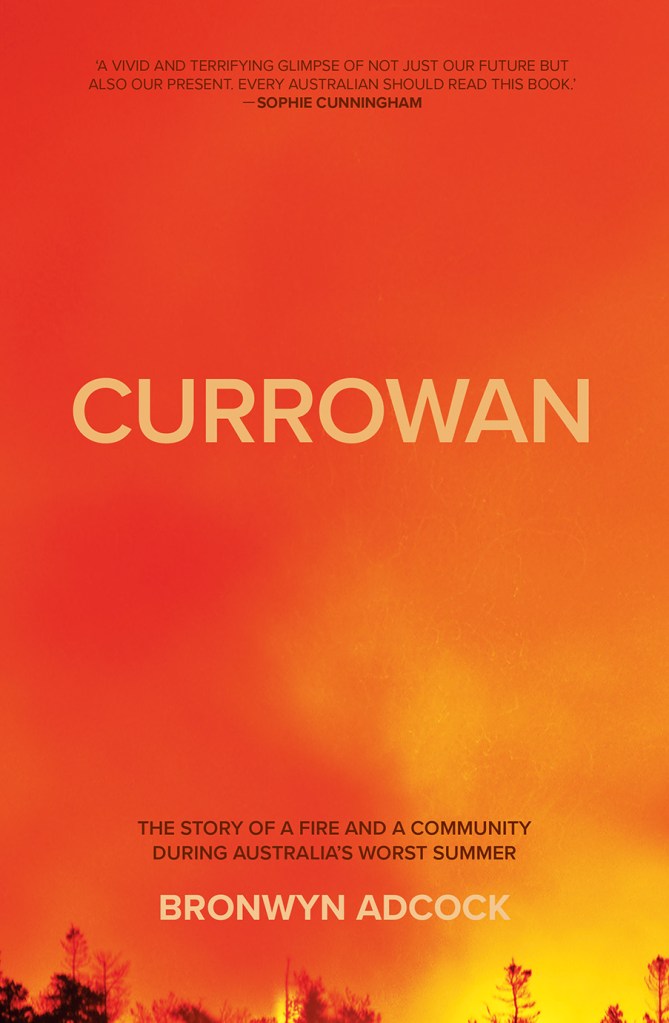

Sometimes a popular publication might have more impact than formal inquiries. IBG member Lyndsay Holme has reviewed an important book for our blog: Bronwyn Adcock’s “Currowan: The story of a fire and a community during Australia’s worst summer” (Black Inc Books, 2021).

He found the book a powerful evocation of this huge and damaging fire, its impact on local communities and what it means for how we we prepare for and deal with bushfire…

A vivid and terrifying glimpse of not just our future but also our present.

Sophie Cunningham, Melbourne-based author

A searing account of surviving Australia’s Black Summer, laced with grim warnings about how exposed the country still is to more catastrophic bushfires.

Michel Rowland, editor of ‘Black Summer’ and host of ABC News Breakfast

A raw account of the Black Summer bushfires, combining vivid eyewitness testimony with a storyteller’s eye for detail and nuance. This story matters: not just as a memoir of loss and destruction and ragged weeks under orange skies, but as a warning for next time. Bronwyn Adcock brings this horror fire season to life, forcing us to ask whether the right lessons have been learned. Accounts like this are essential reading if we are to have any chance of preventing a recurrence.

Scott Ludlam, author of ‘Full Circle’

In Currowan, Bronwyn Adcock very ably moves between personal encounter and emotions and journalistic analysis as she develops this factual account of her experience of the fire from the start of this extraordinarily long and intense fire season. The fire began as a lightning strike on 25th November 2019, in tinder dry vegetation in Currowan State Forest. This was deep in remote and forested public land, adjoining several major wilderness national parks on the New South Wales south coast, in the Shoalhaven local government area. It became a major fire that ran for 74 days, over an area of 499,628 hectares (almost twice the area of Blue Mountains National Park).

The fire directly resulted in the deaths of three people, each of whom were experienced in fire fighting but were overrun by the swift and sudden advance of the fire on a dangerous “blow-up” day. Over 300 houses were destroyed and 178 damaged, as were hundreds of sheds and outbuildings and communications and power infrastructure. Countless businesses were impacted. The fire caused the loss of many millions of native wildlife, farm animals and agricultural lands, with irreparable damage to natural habitats and native plant species.

Bronwyn Adcock lives on bushland acreage, which was badly damaged, just outside of the small village of Bawley Point, near Batemans Bay, an area in the Shoalhaven that was severely affected by the fire. She recounts not only her own situation and emotions felt during the fires but also those of the people from communities nearby.

“Adaptation, or building resilience as it’s sometimes called, is one of the most pressing issues Australia faces. We are one of the most climate-exposed countries in the world – recent research suggests that more than 380,000 existing homes are at high risk of exposure to extreme weather, be it bushfires, flood or coastal inundation. Figuring out how to best prepare ourselves, our homes, our infrastructure is challenging, in part because there is no stable baseline to plan from”. (Adcock)

As I read these lines, I keep wondering where in all this is “Resilience New South Wales”, the recently formed organization designed to address these issues by the state government and headed by the former Rural Fire Commissioner? Adcock writes: “As profoundly shocking as the fire season of 2019-20 was, we are likely to see much worse.”

And so it is that we need to build sustainable building and planning mechanisms and implement them. Already it is happening to some degree within fire-affected communities. In Kangaroo Valley, Bilpin and Cobargo, local residents are initiating community fire planning and self-support groups through local neighbourhood centres. They are pressing local and state government on urgent and relevant needs for safe infrastructure, including adequate access and egress from isolated communities, emergency power generators for small groups of houses and villages and adequate protection around communications infrastructure on the south coast. But nowhere to be seen, it appears, are federal and state governments giving any serious consideration to such concerning community shortcomings two years on from the fire.

“Even just a small amount of aerial resources – a helicopter to stop a new spot fire becoming a problem for another day, another line-scan plane so residents could be warned a fire was coming …could have made a profound difference. It’s hard to see the federal government’s fiddling over (sic – such things)…in the lead-up to the fire season and while the country burned – as anything but colossal negligence.“(Adcock)

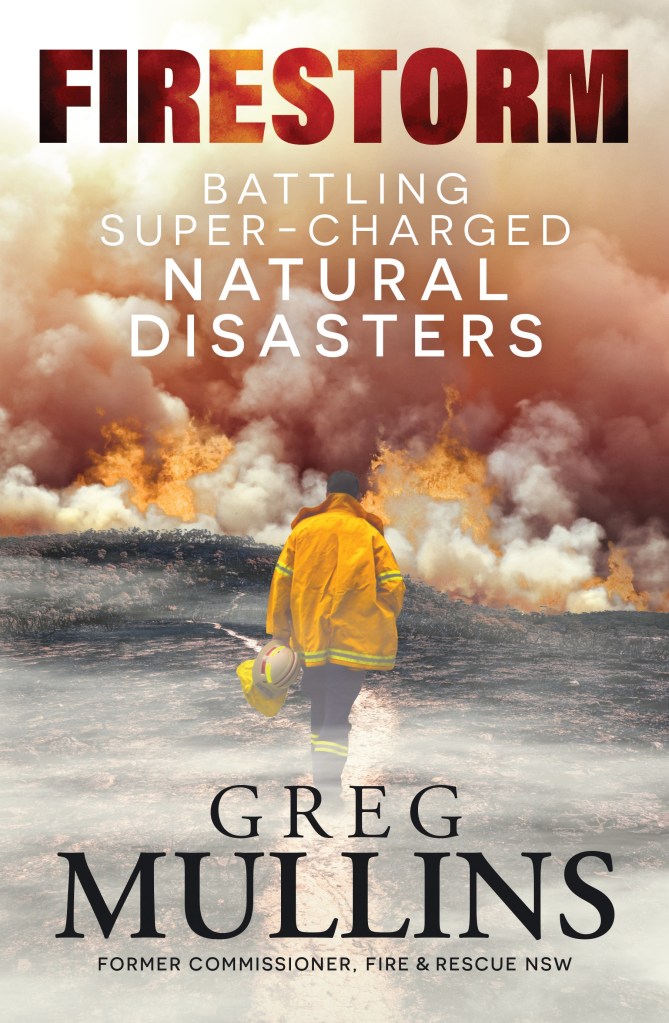

This was despite the repeated warnings from climate scientists, University of Tasmania fire scientist Professor David Bowman, meteorologists and the Emergency Leaders for Climate Change (a group of retired professional heads of fire fighting agencies from across the country headed by retired NSW Fire and Rescue Commissioner, Greg Mullins).

Shoalhaven Bushfire Controller, Mark Williams “maintains his greatest adversary by far was the unprecedented dryness of the landscape. This was land that wanted to burn, incited by extreme weather. ‘What level of resources would we have needed to hold this on any given day? I couldn’t put a figure on it, to be perfectly honest.’”

Adcock conveys the quiet, but slowly controlled anger of many of the impacted, at the lack of initiative and perception shown by many of our country’s political leaders, their arrogant disregard of clear warnings on where we are headed as the reality of climate change impacts on our communities, landscapes and infrastructure. She is passionate but does not lose sight of reality from where she sits in both geographical and analytical observation. She keeps the narrative on track with the developing emergency in her own neighbourhood, but is also clear that this is not an isolated occurrence. She refers throughout the book to other communities similarly affected up and down the east coast and tablelands of Australia, as well as where we are being impacted on a planetary basis.

Communities are pressing governments to act at the same time that business and insurance companies are feeling the financial impact from recurring natural disruptions and the population has to dig deeper into their collective pocket. Risk management is playing an increasingly larger role in initiating pressure on governments to respond to the reality of climate change impacts world-wide. An economic argument is the strongest one to ensure that governments react urgently and responsibly towards the citizens they represent.

This publication is a strong, thoughtful plea for vigilance, planning and preparation for the future at all levels. There are a few minor inaccuracies with her depiction of some details, nomenclature and descriptions of how fire agencies operate, but these don’t detract from her account of how most events played out and how people responded to them. I found her description of “back country” a little folksy; to me it will always be “the bush”. She has consulted widely with the people described in the book, including members of her local community and others more widely known, such as Greg Mullins, Peter Dunn, retired ACT Emergency Services head and resident of fire-affected Conjola Park, and Mark Williams, RFS Shoalhaven Bushfire District Superintendent, who was at the forefront of the Currowan Incident Management Team, together with some of IBG’s former fire fighting colleagues and current members.

“I’ve been watching the 2021 fire season in the northern hemisphere with alarm – it is truly an emergency. To stay sane I try to focus on the small leaps forward – like the way the first boobook owl since the fires has returned to our property, sitting unmoving on a low branch outside my studio, pivoting its head to watch me as I walk up the hill at night.

But mostly I just think, what have we done?” (Adcock)